Doping and English football: A deep dive into the FA’s regulations and challenges

In 2015, The Football Association (FA) claimed to have ‘the most comprehensive anti-doping testing programmes in the world.’

The FA has had the highest number of athletes tested in the United Kingdom. But what do these numbers really mean? The Asterisk highlights the key rules in the FA’s Anti-Doping Regulations and concerns surrounding doping in English football.

What is doping?

The term doping refers to the intentional or unintentional use of banned Performance Enhancing Drugs (PED) by athletes to gain an advantage over other competitors.

English football’s long history of doping

Instances of doping can be traced back to the 1920s in English football.

In the 1924/25 season, Arsenal players consumed ‘pep pills’ before an FA Cup match against West Ham. In 1939, Wolverhampton Wanderers manager Frank Buckley encouraged his players to use intravenous injections. Stoke City’s Stanley Matthews admitted using amphetamines before an FA Cup encounter against Sheffield United in 1946.

In 2005, Middlesbrough’s Abel Xavier became the first Premier League player to be banned for using performance-enhancing drugs. He was suspended for 18 months for using the anabolic steroid dianabol.

Chelsea’s Adrian Mutu was banned for 7 months for consuming cocaine during the 2003–04 season, which is considered a recreational drug.

FA’s Anti-Doping Regulations

All players and participants (anyone involved in the sport such as coaches, medical doctors, etc.) have to strictly follow The FA’s Anti-Doping Regulations.

Under these regulations, The FA aims to protect the physical and mental well-being of the players, uphold and preserve the ethics of the game, and ensure that all teams have a fair chance at competing.

The FA works together with UK Anti-Doping (UKAD), a national body that manages and implements doping policy in the country along with FIFA to ensure that the sport is clean.

What are the doping violations and their consequences?

The following rules are key to the Anti-Doping Regulations and apply to all players and player support personnel for a minimum of 12 months from the date on which they become a participant in the sport.

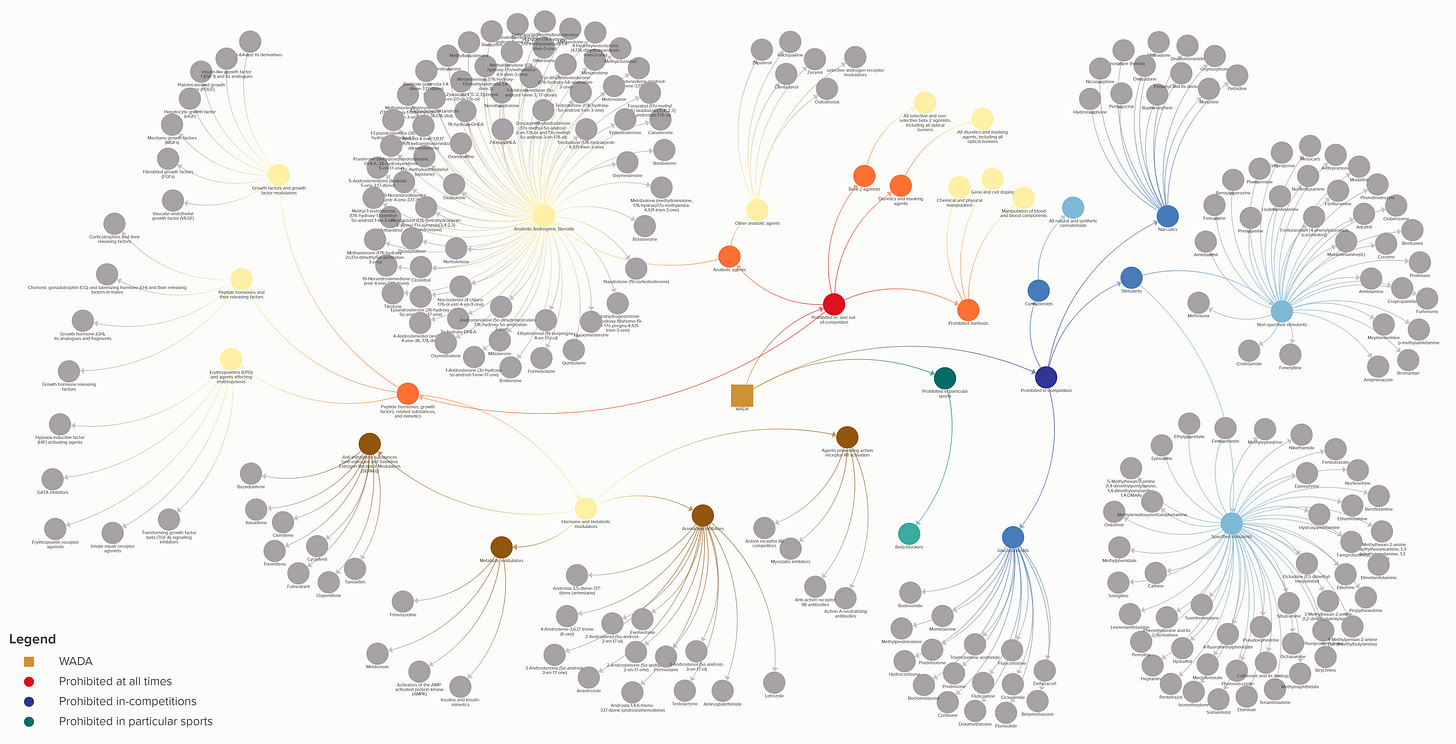

What are the prohibited substances and methods on WADA’s banned list?

The prohibited list is published by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). It bans substances and methods that are prohibited during competitions and out-of-competition. These substances and methods have the potential to enhance the athlete’s performance or hide drugs in their system, which is called masking.

How and when are doping tests conducted?

A player can be subject to in-competition and out-of-competition testing at any time and place set by FIFA, WADA, FA itself and/or UKAD.

The testing process can include but is not limited to urine and blood tests. Players are subject to ‘no notice’ tests, wherein the organisation conducts a test without giving the player any advance notice.

“UKAD runs the FA’s doping programme,” Edmund Willison, a journalist dedicated to investigating doping and sports medicine, told The Asterisk.

“It is their decision how much testing they perform and which substances they test for. The FA just delegates everything to UKAD.

“But when you test positive and you have to go to a hearing, you are going up against the FA, so it will be the FA that sanctions you, even if it’s UKAD that has prepared the case.”

Decisions on anti-doping violations can be appealed by the player, FA, UKAD, FIFA, WADA, or another relevant organisation.

Low cases in English football

In recent years, there have not been many cases of doping in English football.

An i-News investigation revealed that nearly half of professional players were not tested for Performance Enhancing Drugs (PED) after games in the 2022–23 season.

“There’s never been any debate about doping in football because there aren’t enough cases,” said Willison.

“Football needs to simply start by testing more. They’re not doing enough tests in total compared to other sports.

“If you’re a top-level 1500-metre runner or 100-metre runner in World Athletics’ testing pool, then you’re going to be tested like 15–20 times a year.”

Footballers tested more but not frequently

UKAD’s latest testing data reveals that 1,789 tests were carried out for various sports from 1 October to 31 December 2023.

714 tests were conducted on behalf of The FA, which was the highest when compared to other sports disciplines.

“The FA always used to say that there were more tests which were performed in football than in any other elite sport,” Professor Ivan Waddington, a world-renowned expert on doping in sport, told The Asterisk.

“It is true, but there are more professional footballers,” he said and added that there were far fewer athletes in other sports.

“The real question is not how many tests do you do, but how frequently are your athletes tested in the course of a year or season?”

Professor Waddington revealed that some players would not be tested at all for years.

“With a bit of luck you could go two, three, or four years without being tested,” he said.

“So that’s (testing) not really very much of a deterrent.”

Footballers rarely banned for testosterone

Footballers are rarely banned for testosterone, a performance-enhancing drug, according to Willison.

“The public has the impression that every doping sample is tested for every substance, but that is not the case,” the investigative journalist said.

“In football, not many samples are tested for erythropoietin (EPO: a hormone that is used to improve endurance), and very few are tested for human growth hormone.”

“All anti-doping agencies, effectively, don't test directly for testosterone,” said Willison. “They screen for testosterone, and there they measure your ratio of testosterone. It's called a testosterone-to-epitestosterone ratio.”

This ratio is used to detect the misuse of synthetic testosterone in the doping control process. A person with a 1:1 ratio or similar is considered healthy.

“And if it's above 4:1, then you're suspicious,” said Willison. “They do a further test to confirm the presence of it.

“But the problem with that is it's quite easy to stay below that ratio (4:1). You still may be taking testosterone.

FA can invest more to detect testosterone

Willison suggested that every sample should be tested for testosterone through a process called the IRMS (Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry) method.

“It's very expensive, and no anti-doping agencies do that in the WADA system,” he said.

An organisation in boxing called Voluntary Anti-Doping Association (VADA) employs this method.

“It tests every sample for testosterone, and they have a far higher catch rate,” said Willison.

“As for football and all of the anti-doping organisations, they haven't found a way to make these tests cheaper.

“And therefore, they're giving footballers the opportunity to take testosterone in a way that they wouldn't be able to if they were performing IRMS testing on every sample.

The revenues of agencies like VADA dwarf that of the FA, whose turnover for 2023 was £482 million.

“If you really want to tackle doping, you obviously spend more money. The Football Association has a lot of money to do that,” said Willison.

‘Performance-enhancing drug use low in football’

Professor Waddington stated that use of PED’s is relatively low in football.

“This is because the benefits of taking drugs are so much less in football than the benefits in cycling, weightlifting, sprinting, etc.,” the professor at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences said.

“However much you give (drugs) to a guy, it’s not going to make him a better player. It might make him a fitter player,” he added.

But players are abusing another kind of drug according to the doping expert.

“We know that many more (players) take recreational drugs,” he said.

In March, i News reported a big spike in players testing positive for recreational drugs.

Between 2019 and 2021, 10 players were detected for recreational drug use. The violations rose to 39 from 2021 to 2023.

Possible widespread use of intravenous infusions

The use of intravenous (IV) infusions in football is not spoken about, according to Willison.

Infusions are fluids that contain vitamins, electrolytes, or other substances and are injected into the bloodstream through drips or a needle. They can help athletes with recovery, enhance performance, and even mask prohibited substances.

Since 2012, players have been banned from injecting infusions over 100 millilitres over a 12-hour period.

Willison termed the problem a big concern.

“It was a widespread part of football before 2005, and there's evidence that it's continued,” he said.

A recent study by sports doctors, including consultants from Tottenham Hotspur and Newcastle United, raised concerns about the use of intravenous infusions for recovery and matches.

“It's less serious doping in that it's not blood doping or steroids,” said Willison, “but it is doping, and there seems to be a suggestion that it is still widespread.”

Less suspensions in top-flight, more in lower leagues

English football has a strange discrepancy over the number of players sanctioned for banned substances between the Premier League and the lower divisions.

No player was found or sanctioned for prohibited substances in the top-flight between 2015 and 2020, according to the Daily Mail.

Willison stated that 67% of the players that failed a doping test in the lower leagues were sanctioned over the same period.

“In the Premier League where there’s more doctors, better facilities, more people looking after them, you have zero percent who have effectively been more careless by not checking what medication they’re taking,” he said.

More testing required to combat doping

Professor Waddington reiterated Willison’s point of the need for more testing if the FA wanted to improve its anti-doping regulations.

“Let’s say you’re a Premier League footballer, you’re playing 38 games a year, plus cup games, so you’re playing 50 plus games a year. If you reckon that on average, you’re probably going to get tested once every two years, you’re going to be tested one game in 90.

“And because you got an FA Cup semi-final coming up, there’s a temptation to use the drugs because you know that the chance of actually being caught is fairly minimal.

“So it has to be made much more of a deterrent,” he said. “The only way you can do that is by making sure that every player is tested, not just once a year, but two or three times.”

No notice testing, but clubs were aware

In the past, clubs had an idea when a potential dope test would occur, revealed Professor Waddington.

Organisations that conduct these tests are not supposed to provide the athlete any advanced notification about having to hand a sample for testing.

“There were persistent stories that the test always came around on Monday morning after the weekend games,” said Professor Waddington.

“The clubs and the FA always denied that.

“I talked to people who were in very senior positions in anti-doping in the UK, and they told me off the record that ‘yeah, we go around Monday mornings in the club. No clubs know when we're coming, so it has to be genuine.’”

“If people had taken drugs before the game on Saturday or Sunday, that might still be in the system on Monday morning,” the doping expert explained.

“If you know when you're to be tested, then you can do things to flush drugs out of your system beforehand.

“That's the whole point of no notice testing,” he said.

More games may push players towards drugs

The addition of more games to the football calendar raises concerns that go beyond player fatigue and injuries.

“The games are getting harder, they’re getting faster,” said Professor Waddington. “The players have to be much fitter and certainly the players at the top clubs who are playing in European competitions, they’re playing more games. That is going to be a constraint which is going to push more players towards using drugs.”

“I think the problem with drugs is not going to go away,” he said.

“We will never have a society without drugs,” renowned investigative journalist Hajo Seppelt told The Asterisk. He heads the doping editorial team of ARD-Dopingredaktion, a major German broadcasting network.

“The only important question is the level and how we are ready to fight it.”

Seppelt said that Germans take doping in sport quite seriously compared to other countries. “In Germany, we have an anti-doping law which is not working very well,” he admitted. “But we have state prosecutors, some of them who are only focused on doping.”

In comparison, the UK relies on agencies like UKAD and has laws that are used to prosecute offenders.

The media’s role in covering doping

Media organisations like ARD are playing a critical role in uncovering major doping scandals. In 2014, Seppelt exposed the systematic doping practices in Russian athletics. Seppelt and his team, along with the New York Times, recently revealed WADA’s poor handling of 23 Chinese swimmers testing positive for a banned substance. WADA has come under fire for its effectiveness and transparency process.

“People know that to get exposed might be social suicide,” said Seppelt.

There has been a decline in news coverage on doping in football since 2020 in the United Kingdom.

It is the media’s job to investigate, hold athletes and sports organisations accountable, highlight any regulatory efforts, and promote transparency.

“They (sports journalists) do not want to lose their contacts,” said Seppelt. “Many of them are simply sports fans.”

While preserving contacts and building relationships to gain access to stories is important for journalists, the reliance of clubs on news organisations for reach has been on the decline. Football teams now have their own social media pages, channels, and websites to publicise any news and content.

The UK also has stringent libel laws. Journalists have to evaluate potential risks that may lead to legal concerns.

‘Doping not a cheating problem but a PR problem’

Professor Waddington believes the fight against doping in sport has long since been lost.

“But you have to maintain this public façade that sport is clean,” he said. “There will be lots of public confidence, government financing, and support.

“Most anti-doping organisations have really, in truth, seen doping, not as a sports problem, not a problem about cheating, performance enhancement, or health, but as a public relations problem,” he said.

“Every time there's a big doping scandal, it's a massive public relations problem, and they don't want that,” he added.